When you pour a glass of milk or take a bite of cheese, does it evoke the sensation of a physical landscape? Can you imagine the aroma of this place, hear its sounds, imagine what it would feel like to walk through it? The terroir of milk that I will identify as flowing from livestock, landscapes, and microbes, comes together in human hands, which combine all these elements and give them expression as cheese.

Cheese styles evolved in the context of the climate, plant life, geography and corresponding agricultural patterns that fit within wider economies. Generations of fine tuning through trial and error have led to the particular microbial compositions, shape, moisture content, as well as texture and flavor of famous cheeses. This evolution happened within the bounds set by a place.

The modern idea that you can make any cheese from any milk, if you follow the right recipe and add the right package of cultures, is an attempt to negate the influence of place. A great cheese is not just a recipe, and it is also not simply a place. It is people, plants, and animals, expressing a place through their bodies, through their lives. Great cheese is an exchange and relationship between a constellation of elements.

Milk is an emulsion in which fat, protein, minerals, sugars, and microbes are dispersed in water. There are also volatile aromatic compounds (VACs), such as terpenes and phenols. Many of the VACs in milk are directly related to the diet of livestock, originating in the plants they eat which undergo fermentation in the ruminant digestive tract.

Milk is the complex base material upon which the gastronomic universe of cheese is built. As the sugars are digested by microbes, fat and protein break down along labyrinthine pathways of flavor development, milk takes off on infinite trajectories. For now, I want to keep our feet on the ground, in the soils, pastures, meadows, and barns where milk originates.

Milk is a tricky drink to write tasting notes for, as its flavors are subtle. To really taste what I am about to explain takes work. You must be willing to visit the farms and alpine pastures, to walk to shepherd camps, to rise before the sun and drink this essence while it is frothy in a bucket that may appear less than sanitary. To drink milk that is still warm from the body of an animal is to experience firsthand the complex web of relationships between humans, livestock, plants, landscapes, and microbes that can give milk unique aromatic traits.

These connections have been severed in most places through the transition to globalized, commodity food systems. The diverse flavor potential of milk has been eradicated by the manner in which dairy animals are fed and milked, and the milk processed and sold to us.

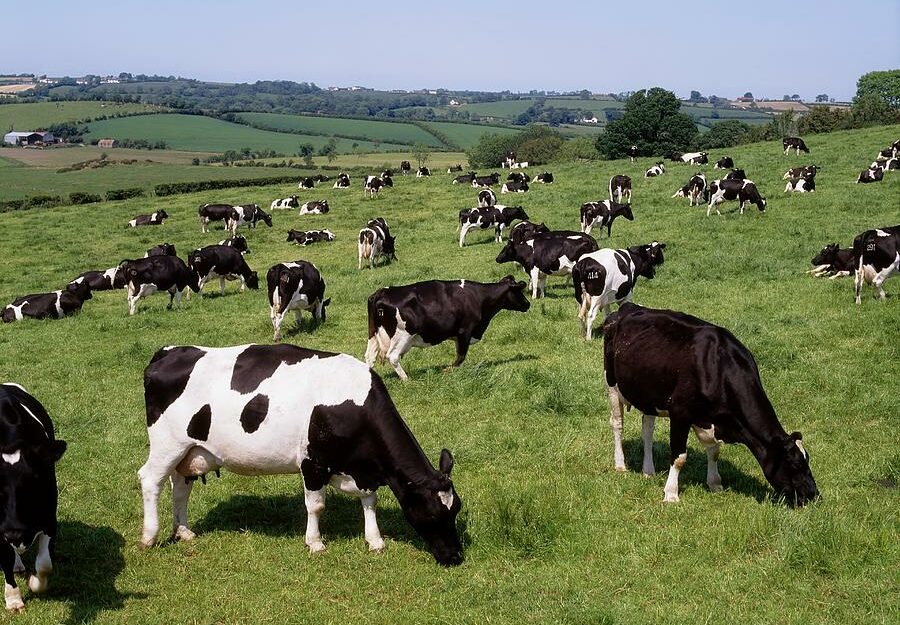

For instance, dairy livestock are increasingly fed a total mixed ration (TMR) which is a mixture of grains, forages, and vitamin/mineral/protein supplements. All the cows in a herd receive the same diet and are no longer allowed to choose from the range of plants available on healthy pasture. You end up with milk that tastes the same year-round, with no reflection of provenance.

This attempt at standardization is intentional, as large-scale production favors uniformity and shelf stability over aromatic nuance or seasonality. We have been trained that we are consumers who value consistency above all else.

However, many of us are pushing back, seeking to explore novel gastronomic experiences while embracing the seasonal variation and inconsistency implied by biology, and reflected in products such as naturally fermented wine and cheese. To seek out the potential for terroir in milk is to begin the work of reclaiming our senses, and to expand our conceptual framework about what milk is, and what it can be.

Most of us are accustomed to the sliced white bread version of milk: the pasteurized and homogenized product of cows raised in confinement on imported feed. Everything has been done to simplify the variables and erase the potential for terroir from this milk.

Increasingly a single type of cow is used, the Holstein-Friesian, an animal bred to produce a very high quantity of milk. This milk tends to be lower in fat and protein compared to that of breeds that produce lower quantities. The cows are often fed on a fermented grass or corn fodder called silage, supplemented with alfalfa and a grain ration designed to meet the high caloric demands of intensive milk production. The emphasis is all on quantity, equations of output versus input.

In drinking this industrial milk, we are still consuming a landscape. It is likely not a single place, but a strange, disjointed cubist mosaic containing patches of the Brazilian Amazon cleared for soy, and perhaps some Canadian prairie beaten to death by generations of plowing to grow GMO corn. There may be a bit of California sun and Colorado river water, used to grow alfalfa in Arizona. This is all brought together in what is likely a concrete-floored, aluminum-sided cattle shed that emits a constant stream of urine and manure.

It is probably better that every attempt is made to remove the terroir from the milk produced in this system. The taste of a place is generally touted as a positive attribute, but we can also discuss negative terroir.

People can be put-off when they taste raw milk that has high levels of olfactory complexity, that actually tastes like the animal and place from which it came. The baseline has been set very low by the one-dimensional flavor of commodity milk. In being denied the experience of tasting how nuanced milk can be, we have become desensitized.

Luckily, we can reformulate our concept of how milk tastes. We can experience firsthand the diversity and greater depth of flavor that is inherent in our foods before they are degraded by the industrial food-as-commodity approach that has caused us to lose our senses.

The fats in milk combine with proteins to give it umami character and textural attributes. For me, I can judge the fat content in milk more by its thickness and the creamy mouthfeel than by its actual taste. The flavors of the fats and proteins in milk become more distinct as they break down during fermentation, or oxidation.

That said, fat content does register in the nose, and it affects our perception of other aromatic qualities in milk. A study from 2022 describes that humans can detect the fat content of milk by its smell, and that the intensity of some aromas increase while others decrease with higher fat levels. The same study explains how various types of pasteurization alter the saturated fat triglycerides in milk, affecting our perception of its aroma.

The scale of industrial dairying, the pooling of milk from animals, and shipping over large distances creates a perfect storm for the spread of pathogenic or spoilage microbes. These issues are dealt with by compulsory pasteurization, which strips the native microbial populations from milk, while altering its chemistry and flavor.

There are various types of pasteurization, with different temperatures and therefore impact on flavor. I encourage moving away from a binary raw versus pasteurized simplicity to more of a spectrum view towards how heat is applied to milk.

The more you heat milk, the more it begins to taste cooked. Higher levels of heat result in the loss of some of the delicate aromas, but also accentuate certain flavors.

Boiling milk brings out more what many consider to be a milky flavor, it bumps up certain creamy/eggy notes. Many prefer these cooked milk flavors, especially in places such as India where boiling milk has a long history.

Essentially, it seems that cooking milk makes the savory fats and proteins more detectable, likely as a result of their degradation. It’s somewhat similar to boiled versus raw beef. The raw beef has a more muted, but potentially more intricate flavor profile. The boiled beef likely has a stronger savory character, while the delicate nuance has to some degree been lost.

Contrary to common belief, the cold storage of milk impacts its flavor and microbial makeup in what I would consider a negative way. Milk is generally cooled immediately from body temperature to 4C or lower. Milk is then kept at this temperature inside a bulk tank, with a mechanical agitator and cooling unit.

Under refrigeration, the microbiota of raw milk is altered, as most bacteria – including those beneficial to cheese and our gut microbiome – are inhibited. What are favored are generally negative, cold loving bacteria. The repeated stirring increases the rate of oxidation, leading to stale, off flavors. Along with shipping and pumping, this results in the degradation of fats, altering the flavor of milk.

Some of the flavors that are likely lost in this processing are the volatile aromatic compounds related to phytochemicals in feed. The pathways through which these compounds enter milk and cheese offer the clearest evidence of a chemical basis for terroir in milk.

Phytochemicals are most concentrated in living plants grown without artificial inputs. When animals feed on diverse pasture or rangelands, they ingest a huge variety of them. Some of these remain intact or are altered by digestion and enter milk. I feel that these compounds combine and lead to flavors can be detected as floral, fruity, earthy, bitter, and/or meaty.

It is hard to disentangle the staggering complexity of this vast choir, and say which individual compounds or plants are leading to specific flavors. But when many of these voices come together, milk can really begin to sing with a choral complexity. It’s generally a subtle song, unless a particular voice crowds out the others. It may be a somewhat loud voice, like that of alliums or mustards.

But given the choice, most dairy ruminants eat a large range of plants that leads to a smooth and complex, but very subtle song in the milk. The song can be a bit confusing and low volume, but it tends to build up and become more distinct if the milk is made into a cheese that is aged for months or years.

A crucial factor in milk flavor is the animal species it is sourced from. It can take a sensitive nose and lots of practice before you can tell the difference between buffalo and yak milk, or sheep versus rich Jersey cow milk. The milk of individual breeds within these species also diverges, mainly in the amounts and ratios between fat, protein, sugars, and minerals. Other layers of complexity are the impact of lactation cycles, weather, hormones, and herd health on milk constituents.

Cow milk tends to be fairly mild in flavor, but the milk of heritage breeds that produce low volumes and are feeding on pasture can be quite flavorful. I recently visited a valley in India where the cow milk from various farms had a smoked ham character. They were all feeding similar cut fodder crops such as sugar cane along with corn silage.

The flavors in milk aren’t always direct correlations to the taste or aroma of their feed. These cows were most likely not snacking on ham. It was a particular expression of a more generic cow milk profile that I equate with the beefy flavor that can concentrate in the yellow fat of a grass-fed steak.

Yak milk is like cow milk, but with the minerality turned up. This milk is rare in most of the world, but in high altitude regions of Mongolia and the Himalayas, it is quite common. I often found it to have a very eggy, slightly sulfurous character. It is rich, somewhere between cow and sheep in terms of fat and protein. Like cow milk, it can have a yellow tint, and possesses the ability to stretch beautifully into mozzarella.

Goat milk constituents vary widely between breeds, compounded by the notoriously broad diet of this animal. They prefer to browse vertically on the woody stems, bark, and leaves of shrubs, trees, and vines that cows tend to avoid. Goats often select plants with bitter, sometimes medicinal compounds, and these stronger flavors can transfer into the milk. Goat milk is often perceived to be less sweet than cow or sheep milk.

There does seem to be a general profile to goat milk. For me it is usually pleasant, a barnyard character and animality. It’s not necessarily the overwhelming buck-like odor that many are turned off by. Those particular aromas can come from a few directions.

Just like fish straight from the water doesn’t smell fishy, fresh goat milk usually doesn’t smell goaty. The fats in goat milk are especially delicate, and readily break apart through jostling during transport, or being stirred by a mechanical agitator in a bulk refrigeration unit. It is generally the resulting short chain fatty acids that lend the particular aromas that together are referred to as “goaty”. This can also happen in aged goat cheeses as fats breakdown, but does not always lead to the particular buck-like character.

In rare cases goat milk can possess these stronger aromas straight from the teat. There is a genetic disposition in certain goat populations that leads to their milk expressing a strong goaty flavor. This trait was actually selected for in Norway, where small amounts of goat milk are often added to the Brunost family of sweet whey cheeses.

This genetic abnormality has been identified and bred out to a large extent. But to this day many older Norwegians refuse to drink goat milk. Others are accustomed to and prefer the stronger goat flavor and lament its loss.

Sheep milk is a luxurious treat and is my personal favorite. It’s generally sweeter, and often twice as fatty as cow or goat milk, making it thicker and noticeably richer. The common underlying flavor is that of lanolin. Think of how wool smells, and mutton tastes. This is generally very subtle, and I find it comforting, as I enjoy wool sweaters and roasted mutton, and have fond memories of working on sheep ranches. It is important to note here that flavor is a subjective interaction with the objective chemistry of a food. What attracts and repels us about food – how we perceive and categorize our experience of it – is psychological, and culturally conditioned.

Donkey milk is rare and commands a hefty price. Many cultures regard it as highly medicinal, and people seek it out less as food and more as therapy for a large range of health conditions. After seeking it for years, I had the opportunity to drink copious amounts at a farm in Serbia. It is thin due to low fat content. The flavor immediately reminded me of the grassy flavor of horse meat. It has a stronger phenolic plant character than any milk I’ve consumed. There is a similarity to the aroma of a donkey as well, but that really shouldn’t be a surprise, and for me is not off-putting.

While traveling in the western Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, I had the opportunity to spend time with two communities of camel pastoralists. Walking with the herders and these tall sensitive quadrupeds on their daily grazing circuits, we would stop periodically to milk a camel, consuming the foam-capped liquid immediately. Like donkey milk, it is thin. It tends to be salty, the level varying depending on the vegetation and availability of water. The flavors stemming from the vegetation seem to be more pronounced than in other milks.

The Raika herders can taste the milk and tell you what plants the camels have been feeding on. Even I could recognize the sweet, stone fruit flavor of Unt Kantalo, the camel thistle, a spiny weed that camels feed on voraciously in postharvest agricultural fields.

I feel the differences between the milks of various species becomes more pronounced as fermentation proceeds. A good way to get a sense of the character of a milk is to taste it in as many styles of cheese as possible. This gives you a more well-rounded perspective and allows you to see the common signature flavors that can perhaps be detected in the milk of a particular species.

As a cheesemaker who works to generate starter cultures from raw milk, microbial terroir fascinates me. Raw milk is home to communities of bacteria that can possess different levels of strength and diversity. There are various contributing sources to what is called the “milk microbiota”. One is the bacteria that live on the udders and teats of ruminants, which inoculate milk as it leaves the body.

There is an exchange happening here with the places where these animals live. Some of the microbes in this community can also be found on the plants and in the soil where the animals feed and spend time during the day. Perhaps even more important are the microbial ecologies of the barn, where animals sleep or are milked. The choice of bedding material and the general health of this environment are a huge factor in the microbial balance of raw milk.

An example of how this biodiversity is negated is the use of iodine. Through sprays and dips, iodine is routinely applied to the teats of livestock. This disrupts the existing microbial communities and influences the microbiota of the resulting milk. In effect, this is an attempt to pasteurize the bodies of dairy livestock. Microbial diversity is seen as inherently negative, as something to be wiped out.

The milk microbiota plays only a small role in the flavor of udder fresh milk, unless there is an issue such as infection or the dominance of a single problematic organism. As the milk begins to ferment, this microbial ecology becomes a major force, transforming lactose into lactic acid, and beginning the cascade of fat/protein breakdown that leads to the flavors of cultured dairy products.

Milk is designed to carry beneficial microbes and immune boosting compounds to young animals, and coagulate in their stomachs so its nutrients can be extracted. It also contains the sugars to feed the beneficial microbes. Fermentation is what milk is designed to do.

A large amount of energy is used in the attempt to rid milk of microbes through pasteurization, then storing it cold so it can be shipped to consumers in the form of sweet drinking milk. This milk eventually will ferment, often through the action of less desirable microbes, ones not necessarily found in the original raw milk.

A whole other path to safe dairy foods is to encourage the milk to sour through the action of these beneficial microbes. There is a long and successful track record of humans turning milk into cheese directly, without any refrigeration, to create healthy, exquisitely varied cheeses that are reflections of the landscapes in which they are made.

In order to bring this all together and ground it, I want to share some stories of the places I have tasted through milk. What I would call “deep terroir” exists when there is a common aromatic signature through many dairy foods. In the most impressive cases, I have actually perceived this signature external to the milk or cheese. These cathartic and immediate sensory experiences have informed this piece. I know deep terroir in milk and cheese is possible, even if I can’t explain exactly how, or science hasn’t got to the point where it can either.

In September of 2021 I spent time volunteering as a cheesemaker in the Slovenian Alps. In Bohinj valley a “Cheese Trail” connects small collections of buildings called Planinas: hamlets in an alpine setting where herders milk cows and make cheese in the summer months.

A particular aroma from my time there is etched in my memory. I first noticed it in both the cheese and the thick sour milk beverage served at breakfast. Then I noticed it coming from the body of a cow and permeating the wooden posts of the milking barn. It is a yeasty, sour milk and cow aroma, with a malty aspect I associate with naturally fermented cheeses (those made without the addition of commercial starter cultures).

What I sensed was a distinct and signature variation of a familiar profile, and one of the more profound instances of terroir in cheese that I have experienced.

I now feel this aromatic signature was due to the interplay of the factors I have identified in this piece. The small herd of cows grazed on unfenced pastures just above tree line. The diversity of plants, the cleanliness of the air and water come together in the antique wood frame milking sheds that are likely reservoirs of terroir.

This milk was never refrigerated, it was made into cheese daily which was pressed on a wood table that was impossible to fully sanitize. The table had a peculiar yeasty aroma, adding a layer and amplifying the terroir from the pasture and milk shed. The evening milk was left to sit overnight, then cream was skimmed to make butter. When the skim milk was added to fresh morning milk and made into cheese, it was already beginning to express the aromatic signature, the taste of this place.

Another paradigm shifting flavor memory was formed when I visited an agriturismo in Piedmonte Italy called Cascina del Finocchio Verde. A cheese is made there called Langhe Sheep Tuma, from the milk of this heritage breed. I walked through the lush green pastures and inhaled deeply. Wool, soil, grass, wet leaves, and sheep manure all mingled in a pleasant and clean aromatic stew.

My host then took me to see the space where the small cheeses age. I leaned in close to one and was hit with an immediate recognition. The cheese smelled remarkably similar to the pasture we had just walked through. This is a no-added-starter-culture cheese, it ferments spontaneously from the bacteria that are in the milk, and perhaps living on the cheesemaking equipment.

I then went and observed milking. The sheep were hand-milked into a pail, which was then carried to the cheesemaking room and poured into a large pot. Cheese was made immediately after both morning and evening milkings. I tasted the milk after each milking and began to discern a profile that linked up with the common theme I had discerned in the pasture and the cheese. It was in the make room and connected aging space that this all coalesced. There was a yeasty aroma in this space, which added the next layer of terroir and tied together the various barnyard, pasture, and fresh milk voices into the song that is this exceptional cheese.

There are some common themes to both stories that point to how terroir in milk is born. It comes together in the human built structures where animals are milked, and cheese is made. It emerges when we interfere with the milk as little as possible and allow the landscape to speak through it.

Terroir in milk seems to be strongest when there is a continuum between where the animals eat, sleep, and are milked, and the areas where the milk is stored or processed. When we completely separate these spaces, and attempt to remove microbes from milk and processing surfaces, it’s no surprise that terroir is less apparent. It’s a question of how much we want to allow biodiversity to exist in milk, and how we manage the variables that go into the flavor of our dairy foods. It’s also a question of how we raise livestock and live within landscapes.

My examples from Slovenia and Italy represent extremes that would be hard to replicate. What I propose is that a middle path can be found, where we can produce food safely while allowing terroir and microbial richness to exist within landscape health and botanical diversity. We can celebrate these linkages, rather than attempting to eradicate them.

Awareness of these interconnections can inform the framework of modern food safety and supply chains, which are in such obvious need of an update. We can expand our vision of what milk is and apply the paradigm shift happening in agriculture and nutrition which shows that microbes are at the root of functioning soils, ecosystems, and human health. I encourage you to get outside to taste, smell, feel, and see where milk comes from.