In 2008, the phrase “echar la persiana” – literally, lower the blind, or close shop – came back into Madrid’s everyday conversation. Spending was shrinking and restaurant eating, which had become a way of life when democracy returned, fell dramatically. By the time economic depression began to lift six years later, over a thousand of the capital’s restaurants had lowered their clattering metal blinds for the last time.

Yet in those same years, say some younger chefs, the city’s native 21st-century food style was born.

“Rents were so low that our generation could finally set up our own kitchens,” explains Javier Goya laconically. Publicity-shy – the antithesis of Mohican-crested madrileño Dabiz Muñoz, the city’s go-to food-face, currently Best Chef in the World – Javier is a powerful insider influence in Madrid’s food scene. In 2013, he and two friends, all with glowing résumés in Michelin-starred kitchens but with no capital, rented two cheap narrow adjacent spaces in a street behind Herzog & de Meuron’s iconic Caixa Forum art gallery.

A New Native Cuisine

Linking the spaces at the back, stripping off plaster to beams, they opened the restaurant with three zingy seasonal menus – called market, a rural walk, and world – plus fine wines by the glass. TriCiclo, as they called the restaurant, was born! Once the loans were paid off, a nearby restaurant threatened with closure asked for their help … then another, and so on, until today they have six in the neighbourhood, each with its own character, plus a gastro-kiosk repairing cycle punctures in the Casa de Campo park. They share Madrid’s signature food style today: modern, unfussy, relaxed and wide-horizoned.

In the 1950s, named restaurants had existed in Madrid only in upmarket districts: the wealthiest area, Salamanca, was to become home to Spain’s first three-star restaurant, Zalacain, while the historic streets below the Plaza Mayor kept a clutch of centuries-old inns, like Botín, which served wood-roasts (asados a la leña) and cocidos (pots-au-feu). To the north of the old town, in rapidly expanding Chamberi, families met in cake-shops and cows were milked in basement dairies alongside home kitchens where dried chickpeas fell noisily into stewpots. These were the sounds of 1960s food, as remembered by novelist Javier Marías.

The Food Movida …

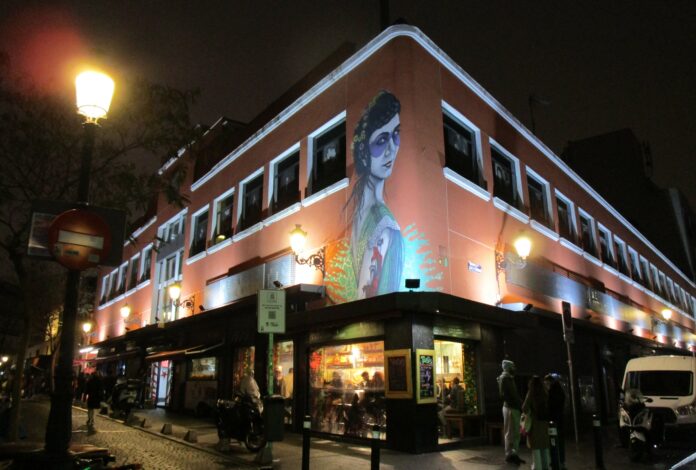

Come the democracy in 1977, and taverns, cafés, bars, and bodegas revived in lower-rent neighbourhoods, or barrios. You could dive into these places, warm in winter and cool in summer, at any time of day or evening, to sit quietly or talk while enjoying a coffee, iced water or small tumbler of wine, plus a bite to eat. Many bites were simple: say, a small round of bread with a slice of fruity, bumpy tomato topped by a few grains of salt, or a chunk of acidic tuna escabeche speared on a stick.

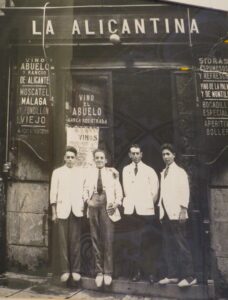

A few places were famed for their hot bites: Café Bravas for its deep-fried patatas bravas drenched in a patented spicy-hot pepper sauce (no roasting or tomato) or El Abuelo, previously aka La Alicantina, where prawns slow-fried in olive oil with garlic in a clay cazuelita are matched with a sweet red wine, a pairing discovered and celebrated by Ferran Adriá.

Friends took me to discover this food in the maze of old streets, which still link the Puerta del Sol with Plaza Santa Ana and Atocha, run north to Malasaña and west to Vistillas. We would explore aperitivos, tapas or late late dinners while flamenco, home-grown rock or witty political chat bounced deafeningly off the walls. Often, we ate standing up, part of a popular food movida and a collective crescendo of voices.

When it came to sit-down meals, however, madrileño cooks cushioned the dizzying pace of change. While Basque chefs led 1970s-80s nueva cocina, then Ferran Adrià shook up the world’s avant-garde from the mid-1990s and Mediterranean chefs stepped up with 21st-century lyrical, luminous cookery, Madrid relished casas de comidas, literally lunch houses, and especially their three-course daily menus, or menús del día. They were so reasonably priced that a funky mixed-generation crowd of family, workmates and friends ate this way right around the city. Everyone could join in: that was the whole point.

Menús del día

The food was good, and high turnover meant that produce was super-fresh: say, fish or calves’ liver griddled or fried in olive oil, crisp-leaved salads, and same-day home-made creamed rice or custards. I remember when the menú del día price, which by law included house wine, tap water, olive oil and a renewable bread basket, was rounded up from 1000 pesetas to 6 euros in 1999. Pessimists muttered, “Se acabo!”. It’s finished.

But it wasn’t!

The menú del día survived both inflation and the 2008 depression to become a start-up tool for chefs setting up on their own at the end of the crisis. Rents and property prices had fallen by a third by 2013, giving young chefs access to space. At the same time, the fixed-price set menu gave high-technique kitchens the chance to offer a limited number of elaborate, very modern, dishes at fair prices.

The format nurtured diners’ trust, allowing chefs to take set menus up into high-end eating.

Take the city’s two Michelin green-star restaurants. At the Sandovals’ family restaurant, Coque, where third-generation farm-to-fork eating meets luxury experience, and at El Invernadero, where Rodrigo de la Calle conjures kitchen-garden produce into magical avant-garde concepts, only degustación menus are on offer. These include a dozen or more tasting courses, but the limited framework, decided by the chefs, as with the three-course menú del día, gives time to focus and bring in dishes at reasonable prices. From a lifetime of habit, madrileños have no complaints with the no-choice format.

The casas de comida have also survived and today they remain havens of relaxed eating, stock-based soups, slow braises, seasonal greenery and fish. Today the best are landmarks (although they rarely get press attention), such as Chamberi’s tiled Casa Ricardo (Est. 1935) and Chamartín’s lunch-only De La Riva (Est. 1932), where executives and builders rub shoulders in a plain dining room revved by high-speed waiters calling spontaneous specials, like wood-roasted peppers or asparagus. Here simple seasonal dishes like stewed lentils, braised tongue, and pears in wine become gourmet eating.

Memory plays at different levels in this breed of restaurant. The hungry years are not forgotten: waiters often urge or coax you to finish the food on your plate.

Stepping sideways, changing pace

While set menus, longer or shorter, nurture a leisurely salt-to-sweet rhythm at Madrid’s mealtimes, today’s younger chefs are changing pace, flavours and locations.

As a sign of the times, in March 2022 the Basque Culinary Center invited two of Madrid’s market-based chefs to speak at Culinary Action, its future-gazing event cooking up new entrepreneurial ideas.

One of the invited chefs, Samy Ali Rendo, aged 43, closed his Michelin-starred restaurant, La Candela Restò, in spring 2019. Just over a year later he set up Doppelgänger Bar in Antón Martín, a two-tier brick and concrete city-centre market a short walk uphill from Atocha railway station. The market, opening every day, sits on the border of Lavapiés barrio, and its kitchen flavours reflect the vibrant local multicultural life. By the time Sami arrived two dozen other kitchens were at work among older produce stalls, offering, among other things, Italian, Mexican and cross-frontier Asian cooking and madrileño aperitivos.

All, however, followed Yokaloka, the pioneer of Madrid’s new-wave market kitchens. It originally set up as a tiny Izakaya sushi stall in 2009. Three years later, in 2012, Dabiz Muñoz set up his second Madrid restaurant, a buzzy, market-style, east-west, no-booking dining-room, StreetXo within a renowned department store.

Why, then, did Samy make a bee-line for Antón Martín market?

Rent, you might expect again. Yes but no: it’s not the whole answer. Emotional satisfaction, family and community are high among market-chefs’ priorities. As Samy put it to journalists, he found working in alta cocina or haute cuisine meant “sometimes smiling, but more often crying”. Setting up a kitchen in a market home meant he could forget security, legal, construction and maintenance issues, all handled by the building’s management, and focus instead on sourcing produce within the market and talking to customers, the big new pleasures alongside cooking.

The Madrid market movement

Two decades ago, nobody saw the Madrid market movement coming. The city’s 46 municipal markets were mainly built or overhauled, scaled and sited immediately before and after the Spanish Civil War, in the early 1930s and 1940s. One market was provided for every 20,000 residents, with others added later to new residential areas on the city’s fringes. In the 1990s the markets seemed to be in decline, like menús del día, but the town-hall tweaked laws to widen their activities and a few years later chefs began moving in.

The fact that the city’s more picturesque historic public markets had been rebuilt or removed seemed a disadvantage. San Ildefonso, for example, the first of Madrid’s covered markets, a private affair, was squeezed into the plaza of the same name in 1835, a year before Barcelona’s Boquería market was arcaded. A vibrant hub famed for its activist verduleras, or vegetable sellers, it was demolished in the volatile 1970s, but many later markets followed its groundplan: long rows of interior stalls ringed by kiosk shops opening on to the street.

Anton Martín (Est. 1941) keeps that design, as does Maravillas (Est. 1933), spread over a single floor at the northern edge of Chamberi. In this hive of 250 stalls, fishmongers, butchers and verduleras predominate, most of them in the old aproned style. A long-standing Spanish bar welcomes you at the front, but much of the excitement is towards the back where two dozen or so Peruvian, Ecuatorian, Venezuelan and cross-frontier kiosks serve breakfasts, mid-morning almuerzos and lunches, mainly to stall-holders and local residents.

Both here and at Mostenses market (Est. 1875, rebuilt 1943), near Gran Vía and Plaza de España, you can eat well at a different Latin American kitchen every day for a week or more. Creative competition has thrown up every kind of arepa, tequeño, ceviche, chaufa, anticucho, patacón, mandoca and empanada as well as Criollo buffets, and Peruvian-Chinese cuisine.

At these kitchens you can simply turn up when hungry, but for the avant-garde Spanish market cookery, you now need to book, just as you do for Madrid’s two dozen or so Michelin-star restaurants. While the latter tend to be packed by visitors to the city – half a dozen of them are in hotels – the crowd at the market kiosks is locally led by curious gourmets, who avoid the polemical so-called “tapas y selfie” patches like Ponzano, Huertas and, above all, the Mercado de San Miguel, a project for tourists run by a Dutch property developer.

Vallehermoso (Est. 1930), for example, a friendly gentrified market in western Chamberi, has earned a place on the city’s gourmet map thanks to Kitchen 154, famed for its slow-cooked spicy-only Asian food, especially its Korean ribs, and Tripea, where an eight-course degustación menu layers Peruvian, Asian and Spanish cooking. Its chef, Roberto Martínez, aged 36, was the second Madrid market guest at Culinary Action 2022.

What all the Madrid market “gastrokiosks” share, whether their cuisine is hi or lo, are menus enriched by attitude and world flavours.

Gastromarkets: the Madrileño Urban Food Hubs

Taking a wider-angled overview of the municipal markets’ stallholders, now nearly 2,800, they are changing the Madrid food landscape at another level.

Each one has a stallholder-association which meets regularly to debate topics like opening days and hours, promotional campaigns, and digital shopping, but these days they also discuss sustainability, recycling, food banks and the markets’ social role.

While Antón Martín and San Fernando (Est. 1944) also in Lavapiés, are now primarily ‘gastromarkets’ although still with some producers’ stalls, other markets, like Barceló (Est. 1942, rebuilt 2014), sited at the epicentre of Madrid’s hip fashion district, have opted to remain principally produce markets. They have great kitchens, but tucked away on the top floor, except a buzzy market-hours award-winning Bistro on the ground floor. The social commitment has so far swung public opinion their way, unsurprisingly given that stallholders here opened every working day during Covid confinements, even when the city ground to a halt following a freak snowstorm.

Amid the gourmet fizz and debate, Madrid’s shoppers are returning to shop in markets. Sensorial pleasure plays a role in this, as does choice. In any Madrid market you can choose between a dozen or more tomatoes of varying variety, ripeness, colour, and appearance, bought in from different growers.

Young customers, many now keen cooks, male and female, also come for the sustainably unpackaged produce and for stallholders’ cutting, boning, and trimming skills for fish, meat, and offal; for the local organic produce; for the ranges of sourdough breads, biscuits and cakes; and for groceries sleuthed around the Spanish regions. Chamartín (Est. 1962) is a reference market for such top-whack produce. Its butchers specialize in native rare breed meats while Peñas offers deli foods worthy of a Milanese salumeria, France’s Fauchon, London’s Fortnum & Mason or Switzerland’s Globus, only here they are packed into two low-key stalls where staff help customers choose between, say, twenty vinegars.

The Madrid municipal markets are, then, in very different ways, reconnecting food supply, professional cuisine, home-cooking and the public food agenda. Three Spaniards, four opinions, runs one saying, and in this case, the more the better. Each market goes its own way, but together they become a plural chorus, with startling soloists, who are reshaping the city’s food culture.

Revisiting the local

More is to come: new market kitchens are flourishing, for example, at the revamped mercados of Tirso de Molina (Est. 1932) in the Puerta del Ángel, and Chamberi (Est. 1876, rebuilt 1943).

Big ideas are also packed into small spaces in long-founded markets. Often, they are produce-led. At La Latina’s raffish La Cebada market (Est. 1875, rebuilt 1956) GelatoLab develops flavours around ripe market fruit; a fishmonger’s deep-frying stall offers excess fish-of-the-day in sizzling Andalusian fritura; and El Tejar serves tomatoes as gourmet stars, sliced to taste, with tuna, anchovies, cured ham, burrata or simply salt and olive oil.

Sometimes little known produce and cuisine are first shared in the city at these tiny market ventures. Maravillas, for example, has given birth to Amazonas, a two-square metre stall offering its fruits, peppers and roots, including Andean potato varieties, and at San Fernando market, where sherry wines are served from the barrel at Bodegas Argueso, you can carry your glass across the aisle to Lingueer, a brilliant African kitchen serving a rolling menu including Senegalese fufu and, Moroccan meatballs with tamarind. The pairing of these wines and food seems natural: sometimes their places of origin are less than 100km apart.

Where, then, does madrileño food fit within these new stretched culinary horizons?

In uptown Salamanca, at the Mercado de la Paz, Casa Dani serves what many consider a platonic tortilla española, or Spanish omelette, firm around the edges and nearly liquid in the middle, though now stickier to comply with health regulations.

Dani’s and Lola’s bar has a remarkable story: it has grown to occupy a take-away kitchen, a sit-down stall, and a restaurant space with a terrace inside the market, all based on straightforward local cooking, like that of the casa de comidas. Founded in 1991, but unexpectedly caught up in the new market buzz, it is now being rediscovered by a younger generation as a refuge of artisanal madrileño food and its little known tecniques, reevaluated in the context of world cooking.

The local, then, can grow within the global – and need I add, of course, that Casa Dani has a menú del día.