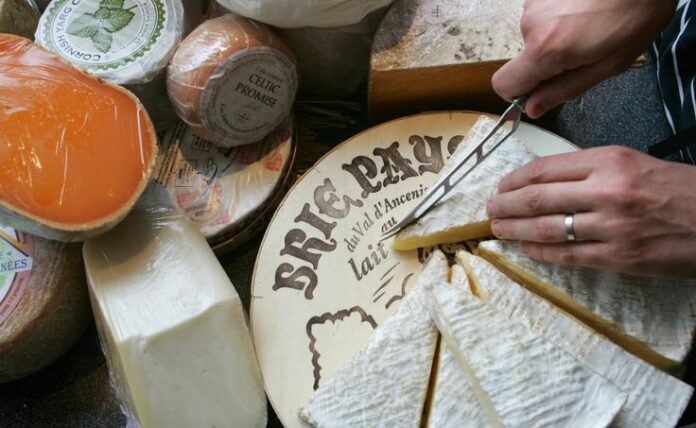

Cheese evolved from ancient survival necessity to regional terroir expression before industrialization standardized production and severed place-based connections. America prioritized volume while Europe preserved regional identities, until the 1980s artisanal renaissance saw American cheesemakers rediscover terroir through farmstead production. Today’s artisan producers face challenges from cheap imitations and regulatory pressures, with cheese choice reflecting values about food and community.

Cheese, as it’s been said, is primordial—an extrapolation of our first food. It evokes the earliest sense memories, while an infinite variation of textures and flavors can punctuate a new experience. Cheese has always been more than cheese. ‘Good’ or ‘bad’, cheese is a manifestation of the human culture embedded in a landscape. It is a perfect model of our relationship with nature, and response to crisis. A real cheese is a feat of reciprocal enrichment while our worst cheese peddles the opposite – joyless consumption, extractive of its source.

Because today, in America, cheese has been drained of value to the point that it often loses the benefit of more careful consideration. Connoisseurship abounds; handmade furniture and beautiful artwork are a backdrop for conversations about small production wines or a chef’s inspired take on seasonal produce. But people are noshing an industrially produced knock-off brie.

How did we get here, given our deeply seated enthusiasm for the stuff? One reason is that industrial cheesemakers can make artisan looking cheeses that go down easy at a fraction of the price. And still, people know real cheese when they taste it. Even an untrained palate will respond with wide eyed appreciation to a great batch at perfect ripeness.

Noted cheese scholar Dr. Paul Kindstedt posits that cheese is not only a hallmark of human civilization—it is a catalyst. About 9,000 years ago humans figured out how to wrangle ruminants, those grazing creatures with the unique ability to extract nutrient from grass. Before we were able to digest the lactose in milk to enjoy it as drink, we managed to slow the spoilage process by acidifying, dehydrating, and salting it. By 6000 BC we had over-farmed the fertile crescent to the point of agricultural collapse. Nomadic cheesemaking allowed early farmers to take their show on the road by taking cheesemaking culture with them as they migrated in all directions.

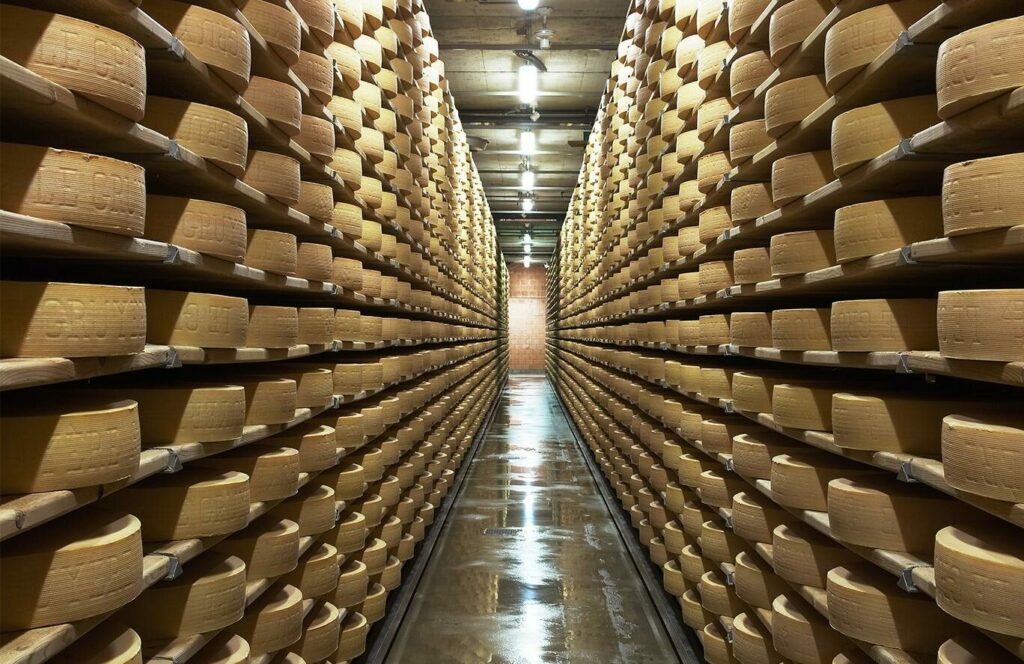

Let’s skip ahead about 7,000 years from cheese inception to Europe, where cellars and caves were used for food storage. The dank coolness was optimized for the discovery of now famous cheese-rind microflora. This coincidence of climate and culture is behind the vast diversity of cheeses associated with Europe compared to other continents. The colonial roots of the United States help to explain the abundance of European cheese on counters here.

Flip through the pages of history to pre-modern times, giving humans 1,500 odd years to achieve localized cheese-style diversification. Dairy animals were selectively bred for their ability to withstand particularities of climate and geography. This resulted in the distinctive breeds still prized today. Recipes were refined to match ripening trajectory with lean seasons or the perils of market access. The forces that shaped regional cheese identity were existential-level threats, not whims of fancy.

Take Alpine Cheesemaking—think firm, smooth textured cheeses like Gruyère. They come from a treacherous landscape, which I’ve personally experienced as a white knuckle drive up a crazy narrow Alpine road with no guard rails. Why bother? So that the arable land down in the valley could be used for enough crops to keep your neighbors alive for another year. This is a very early example of a cheese style resulting from people struggling to set up shop in a new land. Every cheese can be traced back in this way to a style that emerged in a specific place, right alongside the culture and traditions that bore them – a compilation of solutions to a unique set of problems.

The development of regionally identifiable types, often called terroir, was a communal phenomenon – people shared knowledge and resources, working intuitively with animals and microbiology to sustainably glean value from the land. Cheese characteristics morphed to reflect pressures on and preferences of its people. It eventually became both currency and collective self-expression.

However, most of the cheese at the time probably had a challenging profile by today’s standards. With unbridled temperatures, lack of highly controlled rennet harvesting, and imprecise culturing, cheese can get weird and wild. I’m quite certain that cheese grading (this is for cooking, this is for lunch, this is for date night…) is as old as cheesemaking itself. It bears reiterating that cheese was not only sustenance, but it was also currency—a store of wealth for the community.

The motivation to increase palatability and prosperity were one and the same. Our millennia of work to tame the spontaneous eruption of milk into cheese can be thought of as a leveling of the peaks and valleys; some transcendent complexity was probably lost with those truly wild old batches, but the literally gut-wrenching fails are much less frequent.

This ongoing dance of risk and reward is a major theme here because America has a reputation for having managed the reward right out of the equation. For a time though, in the colonial era, deliciousness was the basis of competitive advantage for the Americans. British cheesemakers flew a bit close to the sun as they skimmed more and more cream from the milk to meet a market opportunity for butter. The convention of coloring cheese was originally used to mask the anemic looking result. Customers weren’t fooled, and New England cheesemakers picked up market share with their unembellished, wholesome ‘white’ cheddar.

Another common thread throughout cheese history is the impact of labor issues on innovation. Whether it be the plague, war, or urbanization, communities faced with a shortage of workers figured out new, more efficient ways to fill their cellars with cheese. The endless need to improve productivity per labor hour culminated in the age of industrialization. Pasteurization and improved transport options allowed for milk to be sent farther from farms to larger creameries.

Scaled cheese operations exploded across the US and Europe, fueled by insatiable, growing cities. The age of modernism doubled down, clocking wins for humanity as we triumphantly overcame natural obstacles of disease and geography. Progress, efficiency, and rationality were the guiding principles.

An emphasis on scientific methods sought to ‘improve’ food through standardization and commodification. Terror griped us as we realized microbes exist and indeed were everywhere. Annihilating them, except for the isolated few that helped with essentials like beer, cheese, and bread, became a higher calling of civility. Even those special exceptions would need to be domesticated and commercialized. The order and reason of Science could save us by beating chaotic Nature into submission.

Standardized cheese cultures, developed to replace the native flora lost to pasteurization, effectively clipped a cheese’s tether to any particular place. Thanks to technology, a class of cheeses could safely be made at massive scale in any landscape with near identical results. The pendulum swing of cheese typicity picked up speed in its arc away from wild complexity and towards sterility in form and flavor. Within the course of a lifetime, countless pre-industrial cheeses were lost to the forces of urbanization and industrialization.

Think of this rapid paradigm shift as a mass extinction event of cheeses and their microecologies.

France, having salvaged more of these ‘farmhouse’ cheeses than its neighbors, stands as an exemplary repository of style diversity. As the U.S. stridently focused on sheer volume and homogeneity, European cheesemakers organized themselves around protecting the brand value of regional products – quality over quantity. By 1925 France had established the first AOC for Roquefort and today the EU has hundreds of PDO, or Protected Designation of Origin products.

France, having salvaged more of these ‘farmhouse’ cheeses than its neighbors, stands as an exemplary repository of style diversity. As the U.S. stridently focused on sheer volume and homogeneity, European cheesemakers organized themselves around protecting the brand value of regional products – quality over quantity. By 1925 France had established the first AOC for Roquefort and today the EU has hundreds of PDO, or Protected Designation of Origin products.

This is not to say that European classics aren’t being made in modern cheese plants; production was modernized, but generally in a way that refined textures and flavors and maintained basic regional identity. Cultures were standardized, but with a goal of replicating or bolstering the complexity of raw milk, as opposed to those designed to avoid any whiff of our unclean primordial past.

It should be noted that many Europeans lament a tortuously slow erosion of regional character that has persisted along with these efforts towards organization and preservation. The point I’m making is that their more tempered approach to industrialization stands in stark contrast to the direction American cheesemaking has gone.